I contributed to this little primer on the elections in El Salvador in the newest edition of

Latin News. Most of it was written in early December but it's not clear that much has changed in the month since.

The race for the presidency in El Salvador is in full-swing, with three main contenders representing the incumbent left-wing FMLN, the right-wing Arena, and the upstart challenger to El Salvador’s two-party system, Movimiento Unidad. In all likelihood, the three-way race will lead to a March runoff, because Salvadorean electoral rules require that the winner of the presidency surpass 50% of the vote.

After selecting the moderate Mauricio Funes as its candidate in 2009, the FMLN this year has instead opted for a candidate from the hardline left. A former guerrilla commander from the Popular Liberation Forces ‘Farabundo Martí’ (FPL), Sánchez Cerén is currently serving as vice president, having also held the education portfolio before stepping down to run for the presidency.

In order to balance the ticket, the FMLN selected the popular mayor of Santa Tecla (and also former FPL guerrilla), Óscar Ortiz, as Sánchez Cerén’s running mate. While many outsiders would have preferred Ortiz to head the ticket so as to maximise the party’s chances of winning over more moderate voters, the FMLN remains convinced that the candidate is less important than the party brand.

Norman Quijano, a two-time mayor of the capital San Salvador (2009-2013), will try to recover the presidency for Arena. The party lost it in 2009 having held it since 1989 .Quijano easily won re-election as mayor in 2012, when he convincingly defeated the FMLN’s Jorge Schafik Handal by 63% to 32%.

Quijano’s running mate is René Portillo Cuadra, who in December 2013 denied that he was considering renouncing his candidacy because his views had not been taken into consideration during the campaign. Arena has experienced severe difficulties maintaining internal unity since losing the presidency in 2009, which has undermined support for Quijano and the party.

Former President Elias Antonio (‘Tony’) Saca (2004-2009) is running for his moderate centre-right Movimiento Unidad coalition. Saca is a former broadcaster who served as president of the Arena administration for the 2004-2009 period, a five-year term during which crime increased and the economy slowed. Saca was expelled from Arena after the party’s defeat in the 2009 elections, allegedly because of excessive corruption during his presidential term.

He then established Gran Alianza por la Unidad Nacional (Gana) with several other dissident Arena members. His running mate is Francisco ‘Pancho’ Laínez, who resigned from Arena in March 2013. Laínez served as foreign relations minister during the Saca administration. While Unidad portrays itself as a third party alternative between the FMLN and the Arena, it is unclear what a Unidad presidency would look like. Saca and his supporters are more ideologically aligned with Arena, but they have had a strained relationship with their former allies, with whom they would most likely have to work in the 84-member unicameral legislature to pass legislation. Therefore, some see Unidad as more likely to work, formally or informally, with the FMLN.

Corruption, the economy, the truce negotiated in March 2012 between the country’s two main street gangs (maras), MS-13 and the rival Barrio 18, and relations with the US have dominated the media coverage of the campaign. All three candidates and/or their parties have been linked to ongoing corruption investigations.

President Funes appears to have accepted a US$3m donation from businessman Nicolás Salume during his 2009 campaign, but the details remain unclear. Arena and US officials remain concerned that Funes and the FMLN’s campaigns have been financed illegally by donations from Venezuela and the joint FMLN-Petróleos de Venezuela enterprise (ALBA Petróleos), with the involvement of former guerrilla José Luis Merino, allegedly connected to the Colombian guerrilla group, Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (Farc), and with the appointment of suspicious individuals to positions overseeing domestic security. While his party and the president have come under scrutiny, Sánchez Cerén is the only candidate so far untouched by allegations of corruption.

President Funes has asked prosecutors to investigate former president Francisco Flores (Arena) on charges related to a US$10m donation from Taiwan during his 1999-2004 term. The money was supposed to assist small farmers register their land titles, but it does not appear that the funds ever arrived at the government agency and instead might have been used to finance Flores’ think tank, América Libre Institute. A senior advisor to Quijanjo, Flores was forced to step down in December 2013 in light of these allegations. Quijano himself has been the target of an investigation into his mishandling of funds as mayor of San Salvador. In addition to Flores and Quijano, the attorney general’s office levied charges against 21 individuals accused of embezzlement and falsifying documents, costing the government over US$1bn in losses. The accused include former government officials who served in the Flores administration and businessmen closely connected to the Arena party.

The third candidate in the race, Saca, has not escaped the allegations of corruption. Saca’s personal wealth allegedly increased from approximately US$0.6m to over US$10m during his single term in office. Questions also remain as to the destination of over US$200m in discretionary funds during his administration. Several officials that served in the Saca administration, including former ministers, vice-ministers, government employees, and businessmen, are also under investigation for incomplete work on the highway Monseñor Romero Boulevard.

As president, Sánchez Cerén would most likely continue the reforms begun under the current administration that have benefited the poor and the middle classes. These include subsidies for small farmers, social programs that provide meals, uniforms and supplies to thousands of school-aged children, expanded pensions for seniors, and affordable access to medicine. In all likelihood, Sánchez Cerén would not impede investigations into corruption from previous administrations or into wartime abuses (dating to the lengthy internal conflict between 1979 and 1992). A Sánchez Cerén administration would also try to balance the economic benefits that would accrue through maintaining friendly relations with Venezuela and the US. Sánchez Cerén would probably try to take a stronger stand against US aid conditions too, such as when the FMLN pushed back against the US-favoured Public-Private Partnership Law last year.

Like Funes, Quijano and Arena would most likely work very closely with the US to implement the reforms associated with the US-funded programmes like Partnership for Growth and the proposed second Millennium Challenge Corporation Compact. Quijano has emphasized the economy as a priority and has pledged to kick-start economic growth and improve investor confidence in El Salvador, but how that would differ from the current administration is unclear.

Quijano initially claimed that he would roll-back several of the social programs carried out by the current administration, but has since changed his approach to say instead that he would improve upon their execution. Quijano has been a vocal opponent of the gang truce between the MS-13 and MS-18, which appears to be failing following the discovery in December 2013 of a mass grave containing the remains of over 40 alleged gang victims. Transitional justice and investigations into corruption during previous Arena administrations are unlikely to be priorities of a Quijano administration.

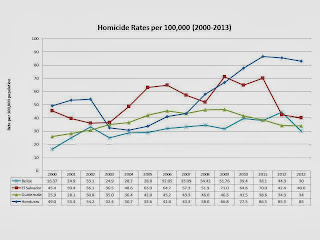

On 7 January President Funes said there had been 2,426 registered murders in 2013, down from 2,543 in 2012 and 4,354 in 2011. That would put the homicide rate at 40 per 100,000 in 2013, compared to 70 in 2011. The president also said that poverty fell four percentage points in 2013 to 29%, on latest census data from the economy ministry. Private economists note that this improvement is due to government social programs, rather than economic growth and job creation, which remains weak.

Real GDP growth in the third quarter of 2013 was 1.6% year-on-year. Annual growth averaged just 1.6% in 2010-2012. The Funes government has deferred tough decisions about its budget, in a country that faces structural obstacles to growth. El Salvador's political cycle (congressional elections are due in 2015) means that the fiscal reforms deemed necessary by the likes of the IMF are unlikely to be addressed properly over the next year. The ratings agency Fitch, which in July 2013 cut its rating on El Salvador (see sidebar), also argues that the political polarisation of the country discourages investment, which has (on IMF figures) stagnated at around 14% of GDP over the last five years or so.